This is going to be a bit convoluted and could be two separate posts but I feel it appropriate to keep as one.

I have been increasingly slow with IDs, and I will probably be far more inactive in the coming weeks. I am going to try and catch up on everything one day, but it will take a lot of time. I decided I wanted to put some explanation out there for why. In part because I feel I should offer an explain of why I am not replying, and in part because I just feel like putting all of my gripes down. There are my two main reasons for increasing inactivity:

1. Have growing need to use time and brain power for more immediately useful life skills

2. Becoming more aware of and frustrated by my own limits regarding bird bone IDing

Point one isn't relevant to iNat but I think needed mentioning, and point 2 ties into the heron pelvises and mandible.

I have encountered this before with the ibis skeleton I found. More recently, with the woodpecker wing. My initial reaction in the field upon finding bird bones is and I think always will be excitement and wonder. But after that, unless it is part of the intersection of the few families and skeletal elements I know like the back of my hand, it's utter confusion.

...

I'm sure crafty technologically inclined people could find a more exact way of searching my identifications to find everything I have IDed as a member of Aves, but that's more effort than I really need for my griping. But, back to the point, the time of writing this, I have 1,383 identifications of Aves annotated with "bone". In the skulls and bones project, I have 2,407 identifications for anything in the class Aves.

Of course, not everyone annotates or allows for observations to be entered into projects. And many of my bird identifications are on observations trapped at "vertebrates" or "animals".

It's not like 2,000 IDs are a lot as far as the iNat bird world is concerned. Many of the birders and ornithologist IDers on here have tens of thousands of bird IDs, if not more. But for me, IDing can take easily half an hour of pouring over my references for comparison, not including the time spent explaining my ID if I find one and making graphics. Sometimes an ID can take weeks of background research. So 2,000 is a lot for me personally. And iNat has a strange habit of eating some of my IDs with comments, telling me I need to sign back in after I have already submitted (even though I am still signed in) and that can be discouraging.

So when I have over 2,000 IDs with many hours tied into them, there is a frustration in being in the field, utterly lost to even guess an order of the bird bone I found. Worse when I return and can't puzzle out through my comparative resources. I understand more specific identification will more or less always depend on comparison, but when I can't even guess order in the field, it gets discouraging.

...

I'm kind of a limited learner. I use illustrations, but they often leave me confused, missing something. I prefer photographs, they feel very effective on the world of iNat or any other little internet corner I might be around on to help with bird bones. But when faced with a physical bone, I realize how limited photographs are too. Especially because I have terrible spacial awareness. Precise measurements are sometimes wholly necessary for species differentiation. But a lot of times I need them when IDing for others on iNat just because I am a terrible judge of size without numbers. I can often be found holding my hand and some bones to my computer screen, trying to parse out what I'm seeing.

I also have pretty bad and sensitive eye sight, which makes me a little living-bird stupid. I am not and never have been a birder. It was hard to find interest in bird watching when I can't see crap without my glasses (which I refrain from wearing constantly because they can give me headaches) and I hate binoculars (because they give me head aches). I learned about a lot of birds inside out first. Nowadays I am more than excited to run and grab my glasses to get a better look at what I think to be our seasonal pied billed grebe visitors, but this interest only started in late teen hood.

This has indirectly lead me to have extremely skewed perceptions of bird sizes. When learning about bones from pictures and rulers, it's hard to realize how small a grebe can be and how massive a loon can be. I am deeply grateful for a dead loon my sister and I found on a vacation, these dead animals help me understand them up close in a way living ones seldom can.

...

All of this is to say, I am no natural at this. My knowledge is hard gained and incomplete. I often feel like I am trying to grasp a new language that is always slightly out of reach. I'm not even going to elaborate on how the MBTA affects this too but I would be remiss to not give it a shout out. There's also the phenomenon I learned of in Olsen's Osteology for the Archaeologist, that many natural history museums would historically keep the skins of the birds and throw out the rest (including of course, the bones). And what is this with the only interest in avian osteology being from archaeology? I love Lee Post's Bird Building book, but even that book he markets to zooarcheology. Everything else he does is more from the lens of natural history, being he got his bone building started with natural history museum whales. I also remember reading a review of Katrina van Grouw’s The Unfeathered Bird from a birder being shocked that they would be interested in the inside of a bird. Am I missing something? I feel like most mammal people know their mammal bones and at least some herp people are deeply knowledgeable about herp bones. I have learned really awesome things from some herp people about lizard bones I've found. Where are the bird people who know about their favorite vertebrate class' bones? I've noticed some into shorebirds tend to be very good with their respective skulls, and I have seen some people on iNat grow their knowledge on the inside of the birds they love. But I have also seen ornithologists say anything from misguided to patently untrue thing about the possibility of being able to ID birds from skeletal elements. I would love to hear why, from a birder, they believe the community's love for birds does not extent to the bones. I am also baffled as to why it appears that no ornithology programs really care that much about bird skeletons. Any textbook I have found for bird bones has been explicitly for archaeology. When I find ornithology books there are often sections on bird skeletons, but I have yet to see much on using them for identification. There are some helpful scraps here and there, I did find some helpful pelvis illustrations in a book once, that was lovely, and I know some bird tracking books include skulls. And perhaps graduate level ornithology courses touch on this more but from what I have observed I seriously doubt this.

Then there is the whole perching bird thing. They are an insanely biodiverse order, and also very illegal to own parts of if they are native to the US, and so my ignorance about them feels to be as vast as the order itself. Skullsite provides many good skulls, but I am mostly out of luck with post cranial. I get very, very frustrated with the passerine. I'm not going that deeper into this but I am the most likely to be unable to help ID passerines.

At this point, I tend to not respond to a lot of my @'s. And I feel bad about that. But I keep them all in links I email to myself. I am deeply grateful for the group of people who @ me a lot, even though I feel less than faithful and diligent. But you are seen, and I am doing background research, and I am thankful for you guys to keep me motivated to push myself to learn and grow more and keep time carved out for iNat even when I work on other stuff. I am quiet and naturally have a withdrawn presence on and off the internet (unless, I suppose, I'm left to my own devices to ramble on my little blogs and journals) but I really appreciate all of you. I am too shy to @ anyone specifically, but if you think you might be included in this, you are.

One day I'm going to try and get through all of them, but that will take a lot of outward inactivity as I get spend a lot of time doing my own behind the scenes research.

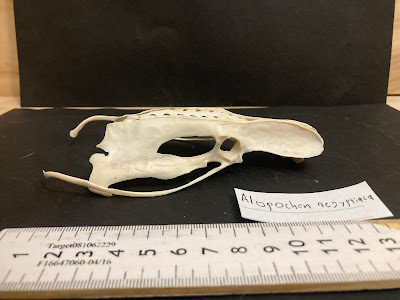

So, how is this massive rant relevant to the heron bones? They were another significant straw of frustration. I want to share my extra pictures of them, but have almost nothing constructive to say about them. Because I just don't know. I have a pdf about differentiating heron pelvises I will review, likely during my planned dormancy. Then I might be able to add something better about them.

So here they are. Another reminder I am standing at a certain precipice of the Dunning–Kruger curve, knowing that there is so much I don't know, and I am afraid that I hardly know what I don't know. Waiting for an avian osetology wiz to join iNat and start IDing and realizing that hasn't happened yet as I look around at bird bones after weeks off and find many messes to fix. I started this journey because I realized no one else was filling this niche. On here and some other places like Project Noah. And I can't figure out why it isn't important to know. A lot of birds are dying. It might be nice to trying and learn from them after they're gone too. Have any of the die hard ivory billed woodpecker believer people looked for recent bones? I'd make sense if they did but I haven't heard much of it. Recent signs of death are signs of recent life. If something lives somewhere, it dies there too. Mammal people I suppose have to use tracks. Mammals are more hidden. Birds seem more obvious. But does that mean their tracks are less useful? Less imperative, maybe. For now. Many academics do keep better eyes on bird remains of course (and I'm still waiting for one of them to join iNat as an amazing IDer to take the mantle of bird bone person away from me), but this area is clearly neglected on iNat and on a handful of other platforms I'm aware of. If a living bird matters, I think a dead bird does too. Its story is just harder to tell.

Ah, Imgur isn't letting me access my gallery. More things to gripe about.

Anyway, here are the bones.

I wanted to edit this more, but I'm realizing my ability to keep up with IDing is slipping faster than I wanted. So I'm going to get this out there sooner rather than later. Apologies for any ramblings that aren't comprehend-able.